By Doug Bennett

Shortening the time spent on the highest-risk football drills could reduce the equivalent of nearly a year’s worth of head impacts over the course of a typical player’s career, University of Florida Health researchers have found.

Using helmet-mounted sensors, the researchers recorded more than 32,000 impacts during Gator football practices and scrimmages in 2016 and 2017. Researchers estimated that shortening time spent on the higher-risk drills by a total of 15 minutes could help players — especially linemen — avoid about 1,000 head impacts during their four-year college careers. The majority of these avoided impacts, about 80 percent, were concentrated within three drills identified as having among the highest impact rates, said senior author James R. Clugston, M.D., a UF associate professor of medicine and a UF Athletic Association team physician. The findings were published recently in the Annals of Biomedical Engineering journal.

The research team, which also included UF Health neurology, neuropsychology and physiology experts, wanted to know if certain football drills had higher rates of head impacts.

“People often paint broad strokes when characterizing the dangers of football and head impact exposure, and a lot of proposed modifications are similarly broad and nonspecific,” said lead author Breton M. Asken, a doctoral student in the neuropsychology track of UF’s clinical and health psychology department in the UF College of Public Health and Health Professions. “There are risks in football, but the risk is not uniform across all activities involved within the sport. Data-driven modifications using a more targeted approach, such as identifying that the majority of head impact exposure occurs during very specific types of drills and activities, could significantly increase player safety without drastically altering the structure of the game.”

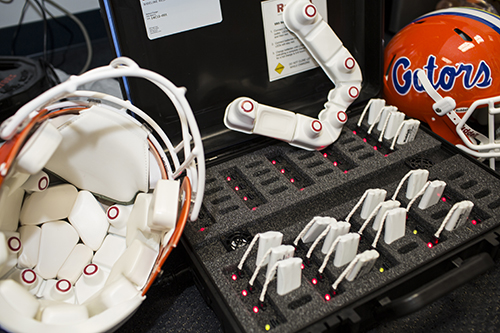

To establish their findings, players’ helmets were fitted with six spring-mounted accelerometers to measure head impacts. Research assistants helped to log all of the players’ specific drills during the 2016 and 2017 training camps and practices.

Linemen had the highest impact rates during the study, which included spring, August training camp and regular season practices. The researchers concluded that minor adjustments to the time spent on drills with high impact rates or live scrimmages would reduce the number of head impacts by almost 1,000 for linemen and 300 for other positions during their college careers.

Clugston concedes shorter practices aren’t very likely to happen in a highly competitive college football environment. However, once a coach knows which drills have the highest risk, substituting time spent on those with lower-risk drills could reduce the exposure. The study found three drills to be especially high-risk: “team run,” a scripted running play from scrimmage; “move the field,” a scenario that spots the ball at different points on the field; and “team,” a series of full-contact, scripted offensive plays.

Reducing the time spent on those three drills by as few as three or four minutes per practice could significantly reduce head impacts, the researchers concluded.

“The athletic trainers we polled were able to identify pretty easily which drills had the highest head impact rates without us even showing them the data,” said Asken, who is currently completing his clinical neuropsychology internship through the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University. “Coaches and athletic trainers should be table to pinpoint where the risk for the highest density of head impacts exists, and can make small tweaks to practice routines to minimize that exposure. That will add up over the course of a season and a career.”

While there are differences in the way college teams conduct practices compared with high school and youth football teams, Clugston said the findings also have potential use for younger athletes.

“It does show that you can look at the drills a team performs and figure out which ones are high-risk,” said Clugston, director of the Sports Concussion Center at the UF Student Health Care Center. “It’s a way of looking at which drills are the worst for head impacts and then designing practices that decrease time spent in these drills.”